It doesn’t have to be lonely at the top.

A private, vetted network where wealth, freedom, and purpose meet.

+1 ,500 members

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

+50 countries

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

01 experience

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

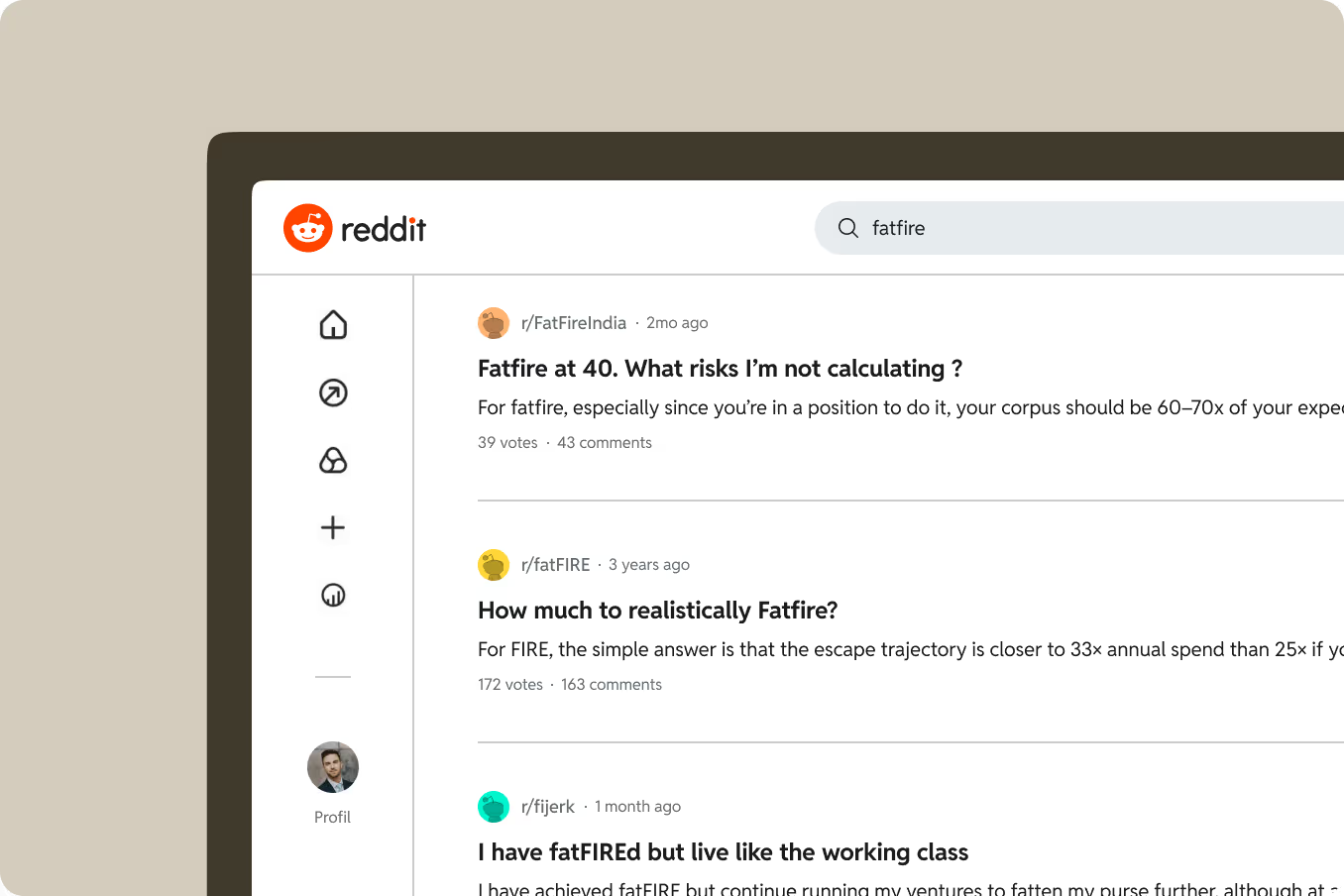

Most networks talk. Few understand.

fatFIRE was built by people who’ve lived it, for those who prefer to live a life that mean something.

Member Pain Points:

Our members often feel isolated in their success and cannot talk freely about their lives (few peers can relate).

Skeptical

They’re skeptical of people’s motives and tired of shallow networking.

.svg)

Struggle to find information

They also struggle to find trusted information for unique challenges (from complex investments to personal matters).

.svg)

Another point

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur. Facilisis aliquet.

Built for those who’ve already made it.

We are more than a service; it’s a high-touch community experience for those who have achieved financial independence and now seek purpose, connection, and reliable support.

A private space for like-minded people.

Upon joining, you’re placed in a curated cohort of around 10–15 accomplished peers.

These small, confidential groups meet regularly to swap insights and support. Share your routine with people who get it.

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

+1 ,500 members

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

+1 ,500 members

It's that easy.

Upon joining, you’re placed in a curated cohort of around 10–15 accomplished peers. These small, confidential groups meet regularly to swap insights and support.

1

Submit Your Application:

Begin by filling out a brief, secure application on our website. We ask for basic information about you and your accomplishments. This is confidential – we never share applicant details.

.avif)

2

Personal Introduction Call:

If it seems like a potential fit, we’ll reach out to schedule a private call. This is a relaxed, one-on-one conversation where we get to know each other.

.avif)

3

Decision & Invitation:

The FatFIRE admissions team convenes and makes a final decision. If approved, congratulations! If for some reason it isn’t the right fit, we’ll let you know and keep your information private.

.avif)

4

Membership & Onboarding:

Approved members will receive a formal welcome packet and an invitation to officially enroll. You’ll pay the annual membership fee and sign a membership agreement

.avif)

.avif)

Be part of it

for yourself

Ready to join?

Selective and private. Join the exclusive fatFIRE club, a community

of like-minded individuals who share your financial journey. Build meaningful connections and a powerful network.

Created for life as it really is.

.avif)

Intimate Peer Groups

Upon joining, you’re placed in a curated cohort of around 10–15 accomplished peers.

.avif)

Concierge Connections

Upon joining, you’re placed in a curated cohort of around 10–15 accomplished peers.

.avif)

Private & Discreet

Upon joining, you’re placed in a curated cohort of around 10–15 accomplished peers.

.avif)

Luxury Lifestyle

Upon joining, you’re placed in a curated cohort of around 10–15 accomplished peers.

Membership Pricing.

Joining FatFIRE.com is an investment in a richer life. We operate as an annual membership service, and because we’re currently in our founding phase, we offer a significant Founding Member rate:

Founding Member Annual Fee

This early-adopter rate is locked in for life as long as you remain a member. We’re capping the initial cohorts at a small number, so founding memberships are limited.

Key Features:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Standard Annual Fee

This early-adopter rate is locked in for life as long as you remain a member. We’re capping the initial cohorts at a small number, so founding memberships are limited.

Key Features:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur

Insights from the inside.

It doesn’t have to be lonely at the top.

A private, vetted network for financially independent individuals seeking more than wealth.